Tamon Castle: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

|City=Nara | |City=Nara | ||

|Prefecture=Nara Prefecture | |Prefecture=Nara Prefecture | ||

|Notes=Unfortunately, there is basically nothing here to see but the sign and the horikiri. The neighborhood below Tamon Castle on the east side, has some old houses and Edo period walls that are actually quite interestering. Luís de Almeida commented on residential quarters which may have been this district for samurai between the mountain and river, see also the Edo | |Notes=Unfortunately, there is basically nothing here to see but the sign and the horikiri. The neighborhood below Tamon Castle on the east side, has some old houses and Edo period walls that are actually quite interestering. Luís de Almeida commented on residential quarters which may have been this district for samurai between the mountain and river, see also the Edo Period map below. While most of the buildings have changed the network of roads is nearly unchanged since that time. The below also includes a couple photos from the hilltop on the west side of the castle. | ||

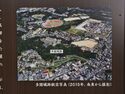

Unfortunately, there is very little to see on the castle site itself today beyond an information sign and a large horikiri cutting across the ridge. Most of Tamon Castle lies beneath Nara Wakakusa Junior High School and | Unfortunately, there is very little to see on the castle site itself today beyond an information sign and a large horikiri cutting across the ridge. Most of Tamon Castle lies beneath Nara Wakakusa Junior High School and the imperial tumuli of Empress Ninshō and Emperor Shōmu. | ||

That said, the area below the eastern side of the former castle between the castle and river is quietly interesting. This district may correspond to the residential quarters noted by the Portuguese missionary Luís de Almeida, who described organized living spaces associated with the castle. This neighborhood preserves a number of older houses and Edo-period stone walls (see map photo below). While individual buildings have changed over time, the street layout remains largely intact. | That said, the area below the eastern side of the former castle between the castle and river is quietly interesting. This district may correspond to the residential quarters noted by the Portuguese missionary Luís de Almeida, who described organized living spaces associated with the castle. This neighborhood preserves a number of older houses and Edo-period stone walls (see map photo below). While individual buildings have changed over time, the street layout remains largely intact. | ||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

|History=In 1559, Matsunaga Hisahide, trusted advisor and lieutenant of Miyoshi Nagayoshi, became daimyo of Yamato Province. His first base was the mountaintop fortress of [[Shigisan Castle]], but in 1562 he completed his masterpiece: Tamon Castle. | |History=In 1559, Matsunaga Hisahide, trusted advisor and lieutenant of Miyoshi Nagayoshi, became daimyo of Yamato Province. His first base was the mountaintop fortress of [[Shigisan Castle]], but in 1562 he completed his masterpiece: Tamon Castle. | ||

Yamato had long lacked a strong, centralized | Yamato had long lacked a strong, centralized ruler. Powerful temples dominated the plains, while smaller lords controlled the surrounding mountains and valleys. Hisahide, who had extensive dealings with Nara’s temples during his service under the Miyoshi, chose to confront this balance directly. He located his new seat above the ancient capital of Nara, overlooking Tōdaiji and Kōfukuji. Temple lands, including Myōken-ji and Saionji, were removed to make way for the castle, and the mountain was renamed Tamonyama after the Buddhist deity Tamonten (Bishamonten). This sent a clear message that warrior authority now stood above religious power. From Tamon Castle, Hisahide could survey much of the Yamato Basin and control the Kyō-kaidō, the vital route linking Kyoto and Nara. | ||

Tamon Castle functioned as the | Tamon Castle functioned as the hub of Hisahide’s castle network. It served as a diplomatic and cultural stage, while [[Shigisan Castle]] acted as the military stronghold. Other castles, including [[Kaseyama Castle]] and Sawa Castle, secured the frontiers. Hisahide was a noted tea practitioner and collector of tea utensils, and gatherings at Tamon included monks, nobles, and foreign visitors. These activities drew on cultural and political skills he had cultivated since his earlier years at [[Settsu Takiyama Castle]]. | ||

Between 1565 and 1568, Tamon also served as a military base during conflicts with the Miyoshi Triumvirate and Tsutsui Junkei. Following victory at the Battle of Tōdaiji Daibutsuden in 1567, in which the Great Buddha Hall was accidentally destroyed by fire, Hisahide secured recognition from Oda Nobunaga as daimyo of Yamato Province. | |||

In 1573, as penance for siding with Nobunaga’s opponents, Tamon Castle was surrendered to Oda control, with Akechi Mitsuhide installed as overseer. Shibata Katsuie and Hosokawa Fujitaka also served as temporary castellans. Nobunaga himself visited in 1574, during which he famously cut the sacred incense log Ranjatai, brought from Tōdaiji and displayed at Tamon Castle. | |||

Soon after, Nobunaga ordered Tamon Castle dismantled. Its most famous structure, a four-story yagura, was transferred to Azuchi Castle. Palatial halls were relocated to the Nijō Gosho in Kyoto, while stone and building materials were reused by Tsutsui Junkei at [[Tsutsui Castle]]. Tamon Castle was absorbed into the emerging Oda framework, and no rival was permitted to stand alongside Azuchi Castle, completed two years later. Many scholars believe Nobunaga drew inspiration from Tamon Castle, while artisans responsible for roof tiles, painted interiors, and metal fittings were requisitioned to work on Azuchi itself. | |||

====Castle Innovations==== | |||

The defining feature of Tamon Castle was its four-story yagura, often referred to as a ''takayagura'' (tall turret). Scholars widely regard this structure as a forerunner of the later castle keep (''tenshu''). Some speculate that a similar ''takayagura'' may have also existed at [[Shigisan Castle]]. | |||

Tamon Castle is also widely regarded as the first Japanese castle to make systematic use of tiled roofs. Drawing on Nara’s long tradition of temple construction, Hisahide employed local craftsmen to produce | Tamon Castle is also widely regarded as the first Japanese castle to make systematic use of tiled roofs. Drawing on Nara’s long tradition of temple construction, Hisahide employed local craftsmen to produce tiles specifically for the castle. Excavated examples differ clearly from contemporary temple tiles, indicating intentional adaptation rather than simple reuse of the temple tile design. Letters written by Hisahide while he was in Kyoto show a particular interest in the progress of these tiles during construction. Thick white plaster (''shikkui'') walls further enhanced the castle’s resistance to fire and weather. | ||

One of Tamon Castle’s most enduring legacies was the development of long, row house-like turrets built atop ramparts. This design became so closely associated with the site that it came to be known as the Tamon-yagura, a form that | One of Tamon Castle’s most enduring legacies was the development of long, row house-like turrets built atop ramparts. This design became so closely associated with the site that it came to be known as the Tamon-yagura, a form that later became standard in Edo Period Japanese castle architecture. In this sense, the castle’s name outlived the castle itself. | ||

Stone foundations for building pillars and stone-lined waterways employed advanced construction techniques, reinforcing the impression that Tamon Castle was intended as a durable, permanent seat of power rather than a temporary stronghold. | |||

In 1565, the Portuguese Jesuit Luís de Almeida visited Tamon and wrote back to Europe in astonishment. He praised the castle’s gleaming white walls and tiled roofs as something “not to be found in all of Christendom.” His letters emphasize that Tamon felt less like a fortress and more like a new kind of urban space. Contemporary records describe lavish residential halls, sliding doors adorned with gold leaf paintings, gardens, and at least two tea pavilions. | In 1565, the Portuguese Jesuit Luís de Almeida visited Tamon and wrote back to Europe in astonishment. He praised the castle’s gleaming white walls and tiled roofs as something “not to be found in all of Christendom.” His letters emphasize that Tamon felt less like a fortress and more like a new kind of urban space. Contemporary records describe lavish residential halls, sliding doors adorned with gold leaf paintings, gardens, and at least two tea pavilions. | ||

|Year Visited=2025 | |Year Visited=2025 | ||

|AddedJcastle=2026 | |AddedJcastle=2026 | ||

|Visits=October 5, 2025 | |||

|GPSLocation=34.69437, 135.83143 | |GPSLocation=34.69437, 135.83143 | ||

|Contributor=Eric | |Contributor=Eric | ||

}} | }} | ||

Revision as of 23:20, 5 January 2026

Unfortunately, there is basically nothing here to see but the sign and the horikiri. The neighborhood below Tamon Castle on the east side, has some old houses and Edo period walls that are actually quite interestering. Luís de Almeida commented on residential quarters which may have been this distri

History

In 1559, Matsunaga Hisahide, trusted advisor and lieutenant of Miyoshi Nagayoshi, became daimyo of Yamato Province. His first base was the mountaintop fortress of Shigisan Castle, but in 1562 he completed his masterpiece: Tamon Castle.

Yamato had long lacked a strong, centralized ruler. Powerful temples dominated the plains, while smaller lords controlled the surrounding mountains and valleys. Hisahide, who had extensive dealings with Nara’s temples during his service under the Miyoshi, chose to confront this balance directly. He located his new seat above the ancient capital of Nara, overlooking Tōdaiji and Kōfukuji. Temple lands, including Myōken-ji and Saionji, were removed to make way for the castle, and the mountain was renamed Tamonyama after the Buddhist deity Tamonten (Bishamonten). This sent a clear message that warrior authority now stood above religious power. From Tamon Castle, Hisahide could survey much of the Yamato Basin and control the Kyō-kaidō, the vital route linking Kyoto and Nara.

Tamon Castle functioned as the hub of Hisahide’s castle network. It served as a diplomatic and cultural stage, while Shigisan Castle acted as the military stronghold. Other castles, including Kaseyama Castle and Sawa Castle, secured the frontiers. Hisahide was a noted tea practitioner and collector of tea utensils, and gatherings at Tamon included monks, nobles, and foreign visitors. These activities drew on cultural and political skills he had cultivated since his earlier years at Settsu Takiyama Castle.

Between 1565 and 1568, Tamon also served as a military base during conflicts with the Miyoshi Triumvirate and Tsutsui Junkei. Following victory at the Battle of Tōdaiji Daibutsuden in 1567, in which the Great Buddha Hall was accidentally destroyed by fire, Hisahide secured recognition from Oda Nobunaga as daimyo of Yamato Province.

In 1573, as penance for siding with Nobunaga’s opponents, Tamon Castle was surrendered to Oda control, with Akechi Mitsuhide installed as overseer. Shibata Katsuie and Hosokawa Fujitaka also served as temporary castellans. Nobunaga himself visited in 1574, during which he famously cut the sacred incense log Ranjatai, brought from Tōdaiji and displayed at Tamon Castle.

Soon after, Nobunaga ordered Tamon Castle dismantled. Its most famous structure, a four-story yagura, was transferred to Azuchi Castle. Palatial halls were relocated to the Nijō Gosho in Kyoto, while stone and building materials were reused by Tsutsui Junkei at Tsutsui Castle. Tamon Castle was absorbed into the emerging Oda framework, and no rival was permitted to stand alongside Azuchi Castle, completed two years later. Many scholars believe Nobunaga drew inspiration from Tamon Castle, while artisans responsible for roof tiles, painted interiors, and metal fittings were requisitioned to work on Azuchi itself.

Castle Innovations

The defining feature of Tamon Castle was its four-story yagura, often referred to as a takayagura (tall turret). Scholars widely regard this structure as a forerunner of the later castle keep (tenshu). Some speculate that a similar takayagura may have also existed at Shigisan Castle.

Tamon Castle is also widely regarded as the first Japanese castle to make systematic use of tiled roofs. Drawing on Nara’s long tradition of temple construction, Hisahide employed local craftsmen to produce tiles specifically for the castle. Excavated examples differ clearly from contemporary temple tiles, indicating intentional adaptation rather than simple reuse of the temple tile design. Letters written by Hisahide while he was in Kyoto show a particular interest in the progress of these tiles during construction. Thick white plaster (shikkui) walls further enhanced the castle’s resistance to fire and weather.

One of Tamon Castle’s most enduring legacies was the development of long, row house-like turrets built atop ramparts. This design became so closely associated with the site that it came to be known as the Tamon-yagura, a form that later became standard in Edo Period Japanese castle architecture. In this sense, the castle’s name outlived the castle itself.

Stone foundations for building pillars and stone-lined waterways employed advanced construction techniques, reinforcing the impression that Tamon Castle was intended as a durable, permanent seat of power rather than a temporary stronghold.

In 1565, the Portuguese Jesuit Luís de Almeida visited Tamon and wrote back to Europe in astonishment. He praised the castle’s gleaming white walls and tiled roofs as something “not to be found in all of Christendom.” His letters emphasize that Tamon felt less like a fortress and more like a new kind of urban space. Contemporary records describe lavish residential halls, sliding doors adorned with gold leaf paintings, gardens, and at least two tea pavilions.

Field Notes

Unfortunately, there is basically nothing here to see but the sign and the horikiri. The neighborhood below Tamon Castle on the east side, has some old houses and Edo period walls that are actually quite interestering. Luís de Almeida commented on residential quarters which may have been this district for samurai between the mountain and river, see also the Edo Period map below. While most of the buildings have changed the network of roads is nearly unchanged since that time. The below also includes a couple photos from the hilltop on the west side of the castle.

Unfortunately, there is very little to see on the castle site itself today beyond an information sign and a large horikiri cutting across the ridge. Most of Tamon Castle lies beneath Nara Wakakusa Junior High School and the imperial tumuli of Empress Ninshō and Emperor Shōmu.

That said, the area below the eastern side of the former castle between the castle and river is quietly interesting. This district may correspond to the residential quarters noted by the Portuguese missionary Luís de Almeida, who described organized living spaces associated with the castle. This neighborhood preserves a number of older houses and Edo-period stone walls (see map photo below). While individual buildings have changed over time, the street layout remains largely intact.

The photos included here also show views from the western hilltop, which help convey the castle’s former dominance over the surrounding terrain, even if the structures themselves are long gone.

Gallery

| Castle Profile | |

|---|---|

| English Name | Tamon Castle |

| Japanese Name | 多聞城 |

| Founder | Matsunaga Hisahide |

| Year Founded | 1562 |

| Castle Type | Hilltop |

| Castle Condition | Ruins only |

| Historical Period | Pre Edo Period |

| Features | trenches |

| Visitor Information | |

| Access | Kintetsu Nara |

| Hours | |

| Time Required | 30 mins |

| Location | Nara, Nara Prefecture |

| Coordinates | 34.69437, 135.83143 |

|

|

|

| Admin | |

| Added to Jcastle | 2026 |

| Contributor | Eric |

| Admin Year Visited | 2025 |

| Admin Visits | October 5, 2025 |