Hagi Castle Town

Hagi: A Castle Town That Shaped Modern Japan

〜萩:近代日本を形作った城下町〜

I first visited Hagi on a whirlwind tour of major sites in the area in 2014. Due to bus delays from bad weather and traffic, I was unable to explore Hagi as I had hoped, and I have always longed to return. From the stonework of the central castle to the remains of great samurai estates turned orchards to the picturesque residences along the Aibagawa River, Hagi is perhaps the best-preserved castle town I have visited. While no original castle buildings remain and only a few samurai residences have survived, the layout of the castle town remains impeccably preserved. In fact, you can still navigate the streets using maps from the 1800s. Beyond the main castle town, the area across the Matsumoto River became a center for early industrialization at the End of the Edo Period, housing shipyards, foundries, and glassworks that reflected the struggle to evolve into a competitive industrialized nation.

I can't cover everything in this brief article, so I encourage you to click through the buttons after each passage for more details and photos.

~Hagi as a Castle Town~

The history of Hagi as a castle town begins and ends with the Tokugawa Bakufu. Unlike many other great Edo Period towns that evolved from thriving Sengoku Period castle settlements, Hagi was newly established by the Mōri clan at the beginning of the Edo Period. After their defeat at the Battle of Sekigahara (1600), the Mōri lost 2/3 of their lands and were reassigned to this extremely remote region. While they had options for establishing their new base, they ultimately chose Hagi due to its natural defenses, access to the sea, and distance from direct Tokugawa oversight. The forced relocation to a remote province fostered anti-Tokugawa sentiment among Chōshū samurai, which may have contributed to their eventual role in the downfall of the Edo Bakufu 250 years later. One legend suggests that throughout the entire Edo Period, the Mōri lord was greeted each New Year with the question, "Lord, shall we attack the Tokugawa this year?"

~Castle Structure~

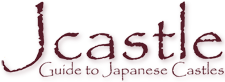

Although the Tokugawa "banished" the Mōri to this remote province, Hagi would have been an ideal location for any warlord's center of power, if it been more conveniently situated. The castle town is flanked by two branches of the Abu River. The rivers and the sea provide natural defenses on all sides. At the tip of the peninsula is Mt. Shizuki, which sits in the farthest depths of the town and is extremely defensible—its only realistic vulnerability is from the sea. This fortified mountaintop provides panoramic 360-degree views, covering the ocean and the surrounding mountains before they descend into the city.

The castle itself is a complex structure, effectively merging two castles into one. In the Sengoku Period, it was common for a flatland castle to be paired with a nearby mountain redoubt (called Tsume-no-shiro). Hagi Castle follows this design. The flatland castle, which includes the honmaru and main keep, and the mountain redoubt are so closely integrated that they function as a single castle complex — one of the most unique and defensible designs I have seen. While some comparable large hilltop castles exist—such as Iyo Matsuyama Castle, which features a similar structure — the key difference is that Iyo Matsuyama's main keep and honmaru are located at the top of the mountain, whereas in Hagi, the primary castle structures are at the plains level making it a rare hybrid between a flatland and mountain castle. Extensive stone walls start with the gates of the Ninomaru and extend along the shores on both sides of the peninsula.

One of this castle's unique charms is the absence of many signs, trails, or fences, allowing visitors to explore freely. Scattered throughout the castle grounds are remnants of old stone walls, often overlooked. Some still bear traces of the clay walls that once stood atop them, though most have eroded over time.

~Tsume-no-maru & Stone Quarries~

The Tsume-no-maru at the top of the mountain was even more well fortified than most tsume-no-shiro with a complete ring of stone walls, two entrances (koguchi 虎口) and seven yagura towers. A distinctive feature of Hagi Castle is that evidence of stone quarrying activities can still be seen today at both the top of the mountain and along the seashore. While many castles sourced some, if not all, of their stone from the immediate area, Hagi stands out for the sheer number of stones that appear to have been left mid-quarry. Seeing this unfinished work is truly remarkable. Nowhere else can you so easily find such abundant evidence of stone quarrying without venturing into remote, hard-to-reach mountain locations with rough terrain.

~Sannomaru Samurai District~

Hagi is an absolute treasure trove of bukeyashiki (samurai residences) from all classes and structure types.

The Sannomaru (三の丸), while technically a castle bailey, was not as heavily fortified in the same way as the Honmaru (main enclosure) and Ninomaru (secondary enclosure), which were protected by stone walls, and moats among other castle defensive structures. Instead, the Sannomaru functioned as a buffer zone, stretching across the peninsula between the central castle and the rest of the town. This area housed the domain’s highest-ranking retainers, including karō (家老, senior advisors) and branch families of the Mōri clan. Many of these former estates were converted into natsu mikan (summer orange) orchards, following the Meiji Restoration - more on that later! These groves not only preserved the original property boundaries but also serve as a visible reminder of the scale of samurai landholdings. While several estates still retain their original gates, the main residences themselves have long since disappeared.

The Kuchiba Residence is the only surviving senior samurai home. When the Mōri clan relocated to Yamaguchi, the Kuchiba family was entrusted with overseeing Hagi, allowing their residence to remain intact through the Edo period.

Before reaching the Middle Gate (Naka-no-Sōmon, 中の総門) that guards the outer moat, you will notice a large two-story corner yagura, larger than some yagura found at other castles. This is a reconstructed corner turret of the Ohno Mōri Estate. The museum also features a faithfully reconstructed nagayamon gate from the Kumagai Residence, which once stood just across the street. These reconstructions provide valuable insight into how samurai residences were not just homes but also integrated into the castle’s defensive network.

Similarly, the Masuda Watchtower, also pictured below, played a key role in guarding the North Gate (Kita-no-Sōmon, 北の総門).

~Sotobori~

Closing off the Sannomaru and the residences of the Mōri elite is the Sotobori, or outer moat. It is a vital yet often overlooked aspect of the castle's defenses. While many visitors may stop by the North Gate (Kito-no-soumon 北の総門), they often bypass the rest of this critical defensive system. The outer moat connects the bay to the north of the castle with the Hashimoto River to the south, effectively cutting off the peninsula at the San-no-maru bailey. With only three gates across the outer moat, it formed a formidable defensive line. Guards carefully inspected those passing through during the day, and at night the gates were shuttered and locked.

~Samurai Residence Walls~

Hagi stands out among Japan's former castle towns for its remarkable number of surviving dobei earthen walls in various stages of preservation or repair. There is no doubt that the extent of these walls are the key factor to helping visitors step back in time. But while these walls remain, the samurai estates they once enclosed have largely disappeared. So, why do we see so many residence walls but so few actual homes?

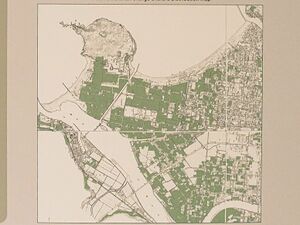

When the Mōri clan relocated to Yamaguchi most of the high-ranking samurai followed. The great estates of these senior samurai were abandoned and the homes fell into ruin. For the lower and middle-class samurai who remained in Hagi, the loss of their stipends brought economic hardship. Enter Obata Takamasa, a former samurai, working for the local township offices. He proposed a new livelihood: cultivating natsu mikan, a large thick-skinned variety of mandarin orange that ripens in early summer. Obata began transforming the abandoned samurai estates into orchards and created an instant success. Since fresh fruit was scarce in early summer, Hagi’s natsu mikan became prized across Japan. Five mikan were worth the equivalent of 1.5 kg of rice. It was said that three productive trees per child could provide enough income for a family to live comfortably and send their children to a good school. The last photo in the set below shows in green just how prevalent mikan orchards were by 1952. They included nearly all the Sannomaru estates and much of the castle compound up to the base of the mountain.

The walls of these estates protected the delicate citrus trees from strong coastal winds. While Hagi’s mild climate and fertile soil were ideal for fruit cultivation, the harsh sea winds could damage trees or knock fruit to the ground. As time passed, these walls were repaired and modified, not necessarily to preserve historical accuracy, but to function as windbreaks for the orchards. This is why Hagi's dobei walls appear in such a variety of shapes and styles today.

Originally built for defense, these walls ultimately safeguarded Hagi’s economic lifeline. In doing so, they inadvertently preserved the authentic atmosphere of a samurai town, making Hagi a rare historical treasure for enthusiasts to enjoy to this day.

~Castle Town~

Throughout the castle town, various areas housed middle and lower class samurai residences, merchant quarters, and temple precincts, all of which contributed to Hagi as a thriving castle town. While the Sannomaru was home to the highest-ranking retainers, samurai of different ranks settled throughout the town. Their residences also served as a castle defense and a means of maintaining order.

One notable area, situated just beyond the sotobori, contained a cluster of residences belonging to influential figures from the late Edo Period, including Kido Takayoshi, Aoki Shusuke Residence (Domain Doctor), Takasugi Shinsaku (military strategist). The Meirinkan, established by the Mōri clan as the domain’s official school, was a center for samurai education, fostering both Confucian learning and military training. Though the original Meirinkan buildings no longer exist, the site was later repurposed in the Meiji Era for an elementary school. However, the Yūbikan (有備館), a martial arts school that was part of the original Meirinkan, still stands today.

Further beyond, samurai estates along the Aibagawa River — including the Yukawa Residence and the former home of Katsura Tarō (general and three time prime minister) — offer a tranquil contrast to the bustling town center. Historically, this waterway was wide and deep enough to allow small boats to transport goods

Among Hagi’s other notable landmarks is Tōkōji, the burial site of five Mōri domain lords and 40 family members. The town also preserves a reconstructed Kosatsuba, where official domain proclamations were once posted, and the gate of Jōrenji, a historically significant structure originally from Jurakudai. This gate, a gift from Toyotomi Hideyoshi to Mōri Terumoto, is an incredible find—easily overlooked yet rich in history, much like the remarkably dilapidated wall in the accompanying photograph. That wall, unexpectedly discovered while cycling through the city, turned out to be part of an unmarked former prison and execution ground—a part of Hagi's complex history.

~Hamasaki Area & Hagi Merchants~

Like many aspects of Chōshū culture, Hagi’s merchant class developed a distinct society, in some ways more advanced than in other parts of Japan. The close relationship between samurai and merchants was particularly unique, as some samurai transitioned into commerce, fostering deep ties between the two classes. Hagi’s merchants played a vital role in the domain’s economy, acting as financial advisors, shaping trade policies, and managing silver mines in partnership with the domain government.

The Kikuya family was especially influential. They served as official merchants (御用商人) and had such close ties with the Mōri government that their residence functioned as a Honjin (本陣) hosting Tokugawa bakufu officials visiting Hagi. The Kikuya had originally helped finance the Mōri’s relocation to Hagi and functioned as a de facto town mayor, overseeing economic and civic matters. Their lavish residence, one of the best-preserved Edo-period merchant homes in Japan, stands as a symbol of their wealth and status. The family’s prominence was so great that Kikugahama Beach, along Hagi’s coast, is named after them.

The Hamasaki district of Hagi thrived as a port town for fishing, shipping, and trade. While several Edo-period merchant houses still stand today, only a few are open to the public. Among them, the Yamamura Residence is noteworthy for its insights into Hamasaki’s role in Hagi’s economy.

The highlight of the Hamasaki area and key destination for castle enthusiasts in this area is the Funagura, or domain boathouse—one of the oldest surviving castle-affiliated buildings in Hagi. This historic structure once housed domain boats used for navigation along the river and bay.

Bakumatsu Period

~Industrialization~

The Bakumatsu period bring to a close the coverage of this website and is the birthplace of modern Japan. By the mid-19th century, Chōshū emerged as a center of resistance against Tokugawa rule and was a leader in industrial modernization.

As Western forces started to threaten Japan's sovereignty, the Chōshū samurai were one of the first to take matters into their own hands and try to modernize and defend their domain from foreign powers.

The Hagi Reverberatory Furnace was built in 1856, but the project was ultimately abandoned before it could produce usable iron. It was too expensive and Hagi lacked some of the knowledge to create an efficient furnace.

The Ebisugahana Shipyard was also founded in the Spring of 1856 and the first western style warship, the Heishin Maru, was launched in December 1856. The second warship, the Koshin Maru, was completed in 1860. Although other smaller vessels were also built here, these were the only two warships built in Hagi. This breakwater has remained unchanged since that time period. It is interesting to see how they essentially used castle stone wall techniques to construct this breakwater. Along the shoreline, excavations have also uncovered the workshops and residences of engineers and craftsmen working on the ships.

The Gunji Cannon Foundry was founded in 1857 to produce cannon, cannonballs, and bullets for the defense of the domain. It was closed in 1868 when country wide arms productions were centralized, but was one of the first successful efforts at mass producing munitions in Japan.

The Onago Battery was one of several coastal artillery fortifications built as part of a defensive network along the Sea of Japan. Constructed in response to the increasing presence of Western ships, it held several large cannon emplacements. The name “Onago” or “Women’s Battery” is said to originate from local accounts that women of the town played a significant role in its construction while the men were away fighting in other battles.

~The Revolutionaries~

While not all of Chōshū’s early industrial projects were successful, they provided a foundation for change and were powerful symbols of modernization. However, Chōshū’s greatest contributions to modernization were intellectual rather than industrial. Chōshū became a breeding ground for revolutionaries who would shape the future of Japan.

Yoshida Shōin (1830–1859) was a brilliant young samurai and radical thinker. By his teenage years, he was already teaching at the domain school, but he grew frustrated with Tokugawa isolationism and longed to study Western knowledge. His early education was heavily influenced by his uncle, Tamaki Bunnoshin (玉木文之進), a strict Confucian scholar and educator who instilled in him a deep sense of discipline and intellectual curiosity.

In 1854, during Commodore Perry’s visit, Shōin attempted to secretly board one of Perry’s ships to escape abroad. Perry refused (fearing diplomatic repercussions) and Shōin turned himself in to Tokugawa authorities. Initially imprisoned in Edo, he was later placed under house arrest in Hagi.

From 1857, while under house arrest, Shoin transformed his residence into a private school known as the Shōkasonjuku (松下村塾). Over the next two formative years he mentored a generation of future Meiji leaders, including:

- Itō Hirobumi – Japan’s first Prime Minister and architect of the Meiji Constitution.

- Takasugi Shinsaku – A military strategist who led the modernization of the Chōshū army. He launched the successful kiheitai which mixed samurai and commoners into one force.

- Kido Takayoshi – A key political leader in the Meiji Restoration. He was also a strong proponent of building the Heishin Maru (see Ebisugahana Shipyard) above and modernizing the military.

Shōin’s radical ideas and defiance of the Tokugawa regime eventually led to his arrest and execution, at the young age of 29, in 1859 for plotting against Tokugawa officials. Though he did not live to see the Meiji Restoration, his teachings profoundly influenced its architects.

In 1863, five ambitious young samurai defied Japan’s isolationist policies and escaped to Great Britain to study Western thinking. These five — who became known as the Chōshū Five — included Itō Hirobumi and Inoue Kaoru who were also students of Yoshida Shoin.

Their escape was made possible with covert assistance from Kido Takayoshi, another of Shōin’s disciples. The Chōshū Five studied Western military strategy, industry, and political systems before returning to Japan, where they became key figures in the Meiji government and industrialization efforts.

~Meiji Restoration~

Chōshū’s alliance with the Satsuma Domain and their superior military strategy played a decisive role in the Boshin War (1868–1869). Their victory against Tokugawa forces led to the fall of the shogunate and the establishment of the Meiji government—a political revolution that brought Japan into the modern era.

And so, we come full circle in the history of Hagi. The Mōri and their descendants, once relegated to the fringes of Japan, became the architects of the nation’s transformation. The Mōri clan moved their base to Yamaguchi, and Hagi quietly faded into history...

Hagi remains one of the most fascinating and well-preserved Edo Period towns in Japan, offering insights into many facets of a castle town throughout the period. Whether exploring the mountaintop castle ruins, wandering through the samurai districts, or uncovering its pivotal role in the modernization of Japan, Hagi provides an unparalleled journey through history.

~Transportation & Visiting Hagi~

Getting to Hagi is half the battle! On my first visit I took the overnight bus from Tokyo which was horribly delayed for bad weather and traffic, losing much of the time I had planned. On my second visit, I took the shinkansen to Yamaguchi and a bus to Hagi where I spent the night and rented a bicycle to fully explore the town over two full days. Hagi is best explored by bicyle. Most major hotels have bicycles you can borrow and there are a few locations around town to rent them too. I used the Meirinkan as my start/end points and rented a bicycle from the Tourist Information Center there.

~Field Notes~

This project marks the culmination of approximately 15 months of work, from meticulously planning my visit to Hagi with maps and routes and questions to ask, to sorting through nearly 3,000 photos and writing the detailed accounts. Between working on this website, visiting new castles and even pursuing other interests, I steadily compiled the historic locations around Hagi into these themes and wrote mini write-ups over the past year — whenever research or inspiration struck. It was only in the past month (Feb/Mar 2025) that I finally brought everything together and started posting these pieces online. I hope everything has come together in a coherent story. It was more complicated than I expected to pull all the different locations and stories together into something that made sense for castle fans. Now, I want to go back again and figure out what I missed!

Hagi’s tourism and historical promotion heavily emphasize its role in the Bakumatsu Period and Japan’s modernization. While this focus is crucial to understanding modern Japan, it sometimes complicates efforts to distinguish what belongs to the Edo Period from what emerged after the Meiji Restoration. Additionally, for many key figures in Japan’s modernization, their legacy is tied to events after the Meiji Restoration, making it difficult to identify their samurai heritage. Given this site's focus on the feudal period, I made a concerted effort to tease out these distinctions, so this narrative focused on the castle, castle town and the samurai who shaped history.

As with any of my feature articles, this one required extensive research, as well as significant investments of time and resources, to craft a cohesive, castle-focused narrative in English. I also reached out to the local tourism organization, which connected me with people at the Meirinkan (Board of Education?) and museum. I even received preservation plans and surveys more than I have had time to go through in detail yet! Their insights helped clarify details and fill in gaps. Since no other English source offers this depth of information, any future guidance you find with this focus likely originated here.

March 16, 2025

~References~

- 萩城 歴史群像名城シリーズ14

- 萩を歩く

- 戦乱中国の覇者・毛利の城と戦略 (1997) 成美堂出版

- 萩市観光協会公式サイト

- numerous pamphlets and signboards from each location