TestPage2

Introduction[edit]

The story of the Battle of Shizugatake is often oversimplified. However, the more you dig into it, the more a fascinating game of chess unfolds across the landscape of Northern Omi. One that would put Hashiba (Toyotomi) Hideyoshi on the road to Kanpaku.

Prelude to Battle (1582–1583)[edit]

On June 27, 1582 (Aug. 2 on the modern calendar1), the Council of Kiyosu was held in Owari, where the distribution of Oda Nobunaga’s territories was decided following his death at Honnō-ji. Yet this meeting failed to stabilize the political situation, it merely ignited a new power struggle to fill the void Nobunaga left behind.

One of the spoils of this reshuffling was Nagahama Castle, originally built by Hideyoshi, it was now controlled by Shibata Katsuie who placed it under the command of his adopted son Katsutoyo. It must have pained Hideyoshi to see one of his beloved castles controlled by a rival.

Hideyoshi was a tactical master. While Shibata and his allies waited for spring, he seized the initiative.

On December 2 (Jan. 11, 1583), under the cover of snowfall, Hideyoshi attacked Nagahama Castle. Katsutoyo was unable to receive reinforcements from Echizen and soon capitulated to Hideyoshi. On December 20, Hideyoshi captured Gifu Castle, forcing Oda Nobutaka to surrender. In January 1583, Takigawa Kazumasa mounted a counterattack in northern Ise against Hideyoshi's aggression. It was also quickly defeated. Toward Echizen, Hideyoshi established an outpost at Tenjinyama Fort to counter Shibata's Genbao Castle. It included satellite forts3 at Chausuyama Fort and Imaichikami Fort to monitor the Hokkoku Kaido and watch for any movement by Shibata.

Shibata must have been chomping at the bit. Seasonal "white demon" (白魔) snows closed the mountain passes to him. He was snowbound in Echizen and unable to open another front against Hideyoshi. Had the three parties linked up or divided Hideyoshi's attention to multiple fronts, Japanese history may have been very different.

Drawing the Battle lines (Spring 1583)[edit]

One of the earliest strategic preparations was the fortification of Genbao Castle, located on the border of Omi and Echizen Provinces. Genbao was notably well designed, suggesting that plans for its construction began soon after the Kiyosu Council. By late February (late March), Shibata Katsuie made the bold decision to mobilize, despite lingering snow in the mountains. What followed was the construction of one of the largest and most intricate networks of mountaintop forts and field fortifications seen during the Sengoku period for a single military conflict.

Shibata's Forward Defensive Line[edit]

Shibata's advance force, led by his nephew Sakuma Morimasa, arrived at Genbao Castle on March 5th (April 10), where they began preparing it to serve as Shibata’s field command. When the main force followed, Sakuma and other key generals moved to Mount Gyoichi to establish Shibata’s primary line of defense looming over Hideyoshi's Tenjinyama.

- Gyoichiyama Fort Sakuma Morimasa

A small stronghold atop Mt. Gyoichi, connected to Genbao Castle by a rugged 3.5km ridgeline.

- Besshoyama Fort Maeda Toshiie

Roughly 1km down the steep slope from Gyoichiyama. Its broad, relatively level terrain allowed it to host a large force.

- Tochidaniyama Fort Hara Nagayori

Situated 400 meters downslope from Besshoyama Fort, acting as a central hub in this line of defense.

- Nakataniyama Fort Tokuyama Hideaki and Kanamori Nagachika

500 meters further down, it provided coverage over the southern slope of the mountain.

Positioned across from Nakataniyama Fort, it supported the northern flank.

- Hayashitaniyama Fort Fuwa Naomitsu

500 meters downslope from Nakataniyama, this fort formed a defensive bulwark along the Hokkoku Kaidō with an embankment over 400m long!

Shibata’s line atop Mt. Gyoichi was reinforced by smaller outposts and field fortifications strung along the Hokkoku Kaidō These acted as sentry points and signal posts, watching for enemy movements from the south.

Hideyoshi's Defensive Lines[edit]

While Hideyoshi was engaged in Ise, he received news that Shibata had started to mobilize. Hideyoshi left Ise to Gamo Ujisato and Oda Nobukatsu and took part of his forces to Kinomoto where they arrived on March 17th. After surveying the Shibata emplacements himself and trying to lure them out, he realized this would not be a quick battle of strength. He abandoned Tenjinyama Fort which was now overshadowed by the Shibata's line on Mt. Gyoichi (see photo above) and established two defensive lines to bottle up Shibata and prevent him from reaching northern Omi.

Hideyoshi established his headquarters at Tagamiyama Castle, roughly 10 kilometers south of Genbao Castle, including forces assembled at nearby Kinomoto Jizoin. This became Hideyoshi's primary staging area under command of his brother, Hashiba Hidenaga.

First Defensive Line[edit]

Hideyoshi created a new forward defensive line centered on Shinmeiyama Fort with satellite fortifications on the same ridge and across the valley. Interestingly, Hideyoshi placed four former Shibata retainers - Ohgane Tohachiro, Yamaji Masakuni, and Kinoshita Kazumoto - who capitulated at Nagahama Castle to command these posts, but the majority of troops were with long time retainer Hori Hidemasa at Tohnoyama.

- Shinmeiyama Fort Ohgane Tohachiro and Kimura Shigekore

Anchored Hideyoshiu's forward line

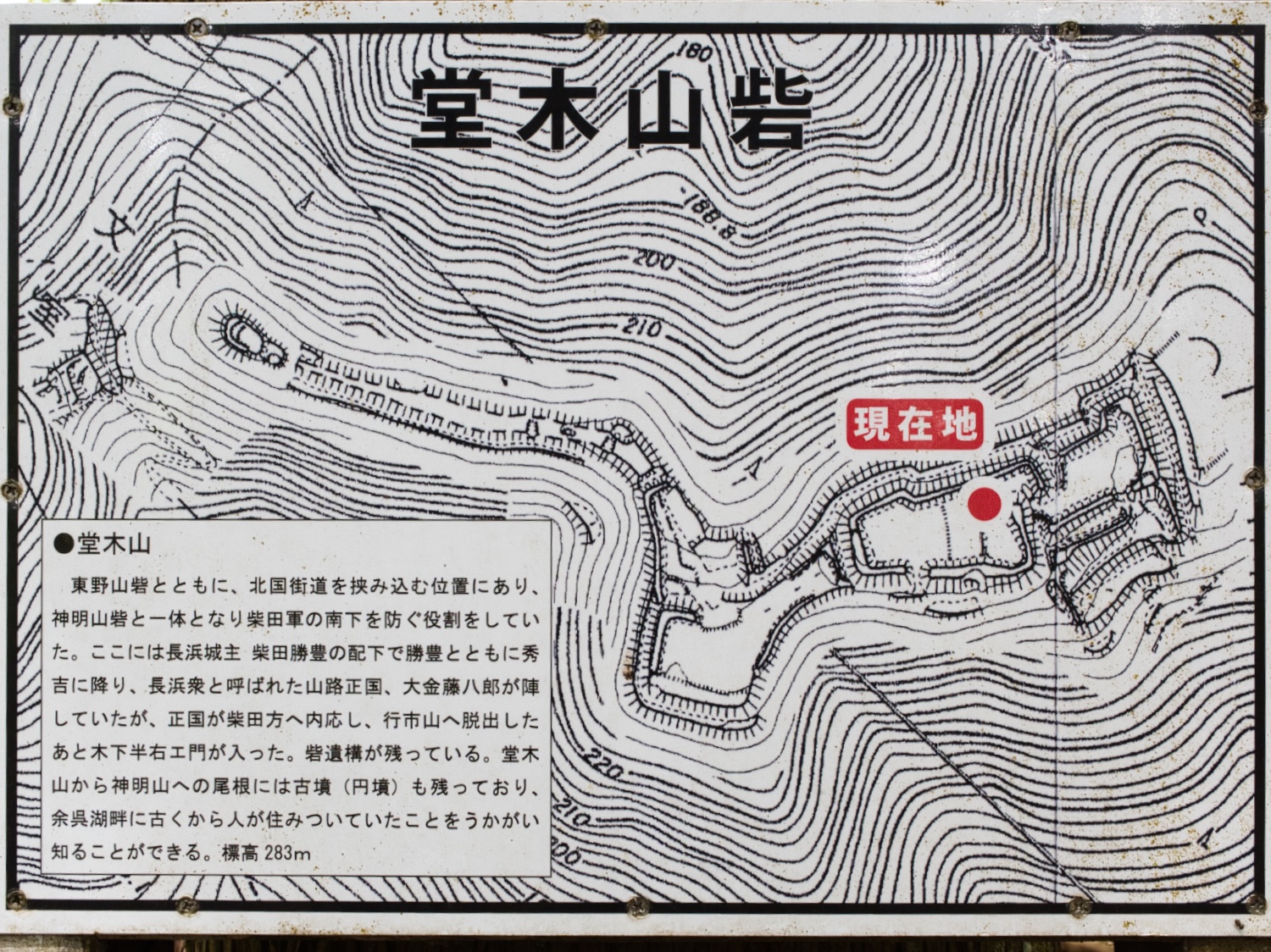

- Dogiyama Fort Yamaji Masakuni and Kinoshita Kazumoto

Spearpoint of the Ridgeline facing the Hokkoku Kaido.

- Tohnoyama Fort Hori Hidemasa

Intricate fort high atop the mountains on the east side of the Hokkoku Kaido, with lower satellite castles at Shobudani Fort and Mizotani Fort

Hideyoshi also constructed a large earthen embankment2 to physically block the road and fortify the narrow chokepoint of the Hokkoku Kaido. Orders were given not to let a single sword past this line.

Second Defensive Line[edit]

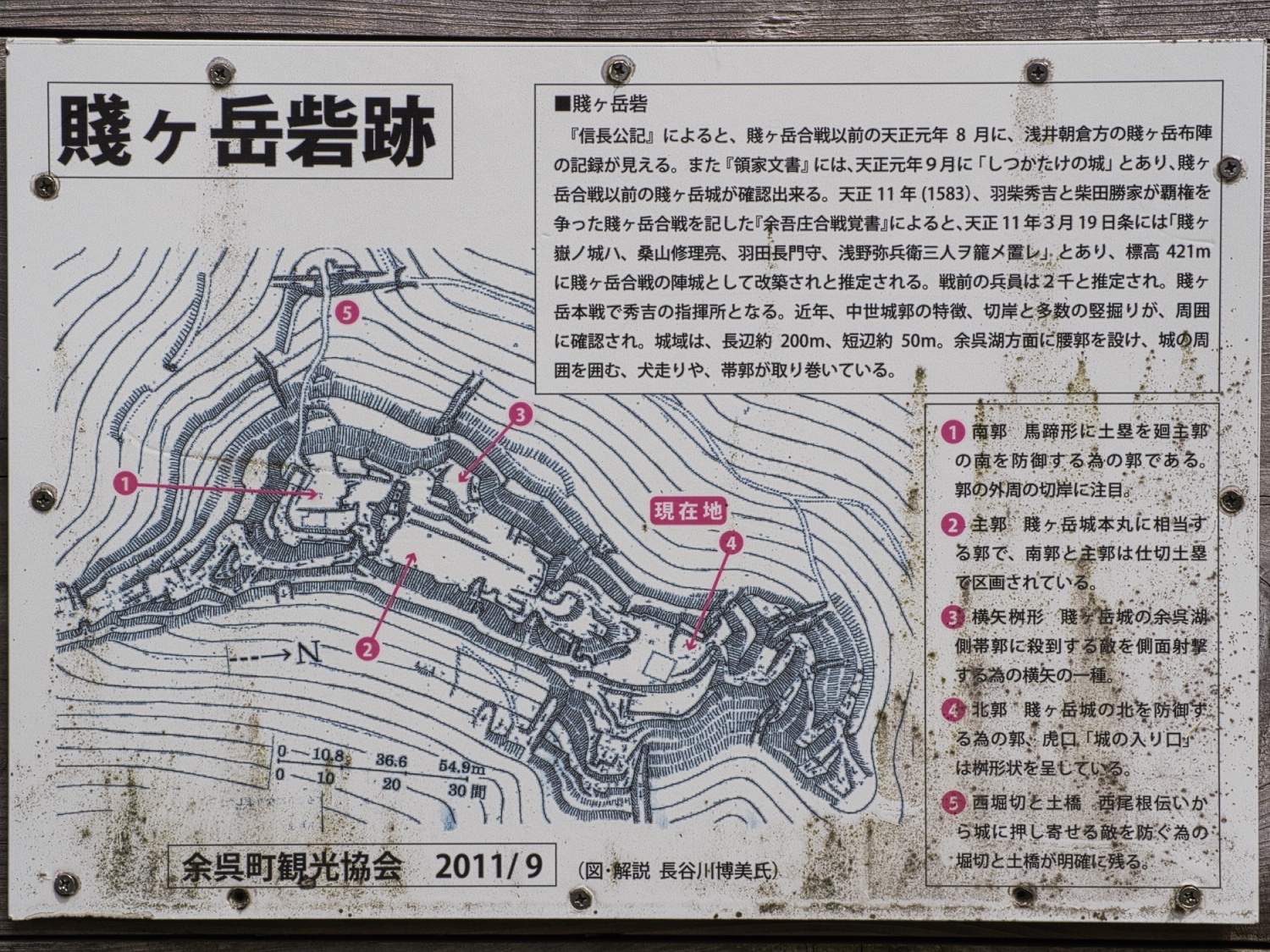

Hideyoshi also created a second defensive line along the mountain range on the shore of Lake Yogo from the peak of Mt. Shizugatake extending north towards the Hokkoku Kaido and linking up with his base at Tagamiyama Castle. These forts are simpler and according to some accounts Oiwayama Fort and Iwasakiyama Fort were not completed at the time of the battle.

- Shizugatake Fort Kuwayama Shigeharu

Fantastic views of nearly every fort and possible route through the mountains into northern Omi.

- Oiwayama Fort Nakagawa Kiyohide

Approximately 2km downslope from Shizugatake

- Iwasakiyama Fort Takayama Ukon

Nearly at the foot of the mountain, this fort watches the highway and prevents attacks on the mountain range from below. At just 1.5km from Dogiyama Fort on the forward defensive line, it could potentially provide backup and logistic support as a midway point to Tagamiyama Castle too.

Niwa Nagahide was also provided 7,000 troops to patrol the Lake Biwa area to prevent any flanking move from the lake. With an overwhelming force and all potential lines of attack secured, Hideyoshi was prepared to wait for Shibata to make the first move.

The Battle Commences[edit]

The stalemate continued into April. On April 4 (May 8), Shibata Katsuie made the first exploratory move by launching a small attack on Shinmeiyama Fort, but Hideyoshi’s forces did not take the bait. The following day, Shibata himself departed Genbao Castle with a large force and engaged Hori Hidemasa at Tohnoyama Fort. A fierce, half-day exchange of gunfire followed, but the other units along the front line did not engage. This was likely a feint designed to prevent Hideyoshi from pulling troops away from the front, indirectly supporting Takigawa Kazumasa and Oda Nobutaka.

On April 13, Yamaji Masakuni and some of his followers escaped and rejoined Sakuma Morimasa, following a failed attempt to assassinate Kimura Shigekore, the commander of the forward defensive line.

With the bulk of Hideyoshi’s army tied down at Shizugatake, Oda Nobutaka and Takigawa Kazumasa reignited their campaigns in Gifu and Ise. On April 17, Hideyoshi entrusted the Shizugatake front to Hidenaga and marched out with 20,000 troops to suppress Nobutaka at Gifu Castle.

With Hideyoshi's departure from the front lines and inside information from Yamaji about fortifications and troop placements, Sakuma Morimasa saw an opening. Shibata was cautious with the highly risky plan but eventually conceded to his nephew's strong will.

In the early hours of April 20 (May 24), Shibata led a sizeable force down the Hokkoku Kaidō to distract Hori’s men along the first defensive line between Tohnoyama Fort and Dogiyama Fort. Under the cover of darknesss, Sakuma Morimasa departed Gyoichiyama Fort to execute his bold mountaintop flanking strategy. Maeda Toshiie was stationed at Shigeyama to guard against any reinforcements from Shinmeiyama Fort. Following the mountain ridgeline, Sakuma circled around the west side of Lake Yogo, bypassing the more heavily defended Shizugatake Fort, and struck directly at the heart of the second defensive line at Oiwayama Fort.

After a fierce battle that saw the death of Nakagawa Kiyohide, Oiwayama Fort fell. Takayama Ukon fled to Tagamiyama Castle, and Iwasakiyama Fort fell shortly thereafter. Even the commander of Shizugatake Fort agreed to surrender at sundown.

The plan had worked better than expected. If Sakuma could hold the second defensive line, many of the troops at Shinmeiyama Fort and Dogiyama Fort (former allies from Nagahama) would likely surrender or switch sides rather than resist. That would leave only Tohnoyama and Tagamiyama forts to contend with.

Shibata’s original orders to Sakuma had been to immediately retreat after the strike on Oiwayama. His goal was to “bloody their nose” and keep Hideyoshi's troops occupied, not to win the war in a single bold maneuver. Perhaps he recalled Hideyoshi’s lightning return from the Chūgoku front less than a year earlier to defeat Akechi Mitsuhide.

But with Hideyoshi away, Sakuma grew confident. He chose to rest his troops at Oiwayama for the night, intending to move into Shizugatake Fort the next morning. Again, Shibata ordered him to withdraw. Again, Sakuma refused, convinced that it would take Hideyoshi at least three days to return from Gifu.

Seven Spears of Shizugatake

賤ヶ岳七本槍

Seven retainers were rewarded by Hideyoshi for their loyalty and accomplishments in battle. Later known as the Shizugatake Shichi-hon Yari (賤ヶ岳七本槍), they became trusted members of Hideyoshi’s inner circle and some of the most influential warlords under his regime.4

- Fukushima Masanori (福島正則)

- Kato Kiyomasa (加藤清正)

- Kato Yoshiaki (加藤嘉明)

- Katagiri Katsumoto (片桐且元)

- Wakizaka Yasuharu (脇坂安治)

- Hirano Nagayasu (平野長泰)

- Kasuya Takenori (糟屋武則)

Unbeknownst to Sakuma, Niwa Nagahide, patrolling Lake Biwa, heard the gunfire and moved to reinforce Shizugatake Fort from the Lake Biwa side. He met up with Kuwayama as they started to abandon the castle but the two held fast instead. When Hideyoshi received word of the attack, he too acted at once. He left 5,000 troops in Gifu and led the remaining 15,000 over 50km in under six hours. The feat became legendary as the Great Minoh Return (美濃大返し).

In the early hours of April 21, Hideyoshi launched a full-scale assault with 35,000 troops. Though Sakuma’s men were isolated, exhausted, and deep in enemy territory, they fought fiercely. The battle devolved into brutal close-quarters combat. Maeda Toshiie suddenly abandoned Shigeyama and retreated toward Lake Biwa, withdrawing from the battlefield. Troops from Shinmeiyama Fort, previously trapped, now surged forward and closed in. Sakuma was surrounded on all sides. The Shibata army collapsed. Soldiers fled. Sakuma was captured and executed.

Shibata Katsuie fled to Kitanosho Castle in defeat. Hideyoshi’s forces surrounded the castle on April 23. Disobeyed, betrayed, and beaten, Shibata set fire to the keep and took his own life, along with Oichi, Nobunaga’s sister, on April 24.

In the aftermath, Hideyoshi moved quickly to consolidate his hold. Shibata’s remaining allies were eliminated or absorbed. Even Maeda Toshiie, who had withdrawn from the battlefield, formally submitted — securing a place in Hideyoshi’s inner circle.

Hideyoshi now controlled Echizen — and emerged as the undisputed successor to Oda Nobunaga.

Interactive Map[edit]

This map is interactive. Click the lines and flags for more details. For the line you may need to zoom in a little to avoid clicking an icon. Distances quoted are direct line distances.

Observations[edit]

Looking at the map, it’s clear that Shibata Katsuie’s forces were unlikely to break through Hideyoshi’s defenses head-on. The forward and secondary lines formed a formidable barrier, blocking all access to northern Omi. With the main bodies of troops stationed at Tohnoyama Fort and Tagamiyama Castle, Hideyoshi could reinforce either line or block the Hokkoku Kaidō as needed. That makes Sakuma Morimasa’s surprise attack all the more bold — and brilliant.

Rather than grinding through a wall of defenses, he descended the mountain ridgeline, directly striking the heart of the secondary line and threatening Hideyoshi’s depleted command post at Tagamiyama, left vulnerable after his departure for Gifu.

It was a truly remarkable feat, one of the most daring tactical gambits of the Sengoku period that I'm aware of. It should be famed on the level of Hideyoshi's water attack Takamatsu Castle or the Great Minoh Return, itself. The route from Gyoichiyama Fort to Oiwayama Fort skirts the west side of Lake Yogo, covering roughly 10km of forested, rugged terrain. Even today, there’s no easy trail. The ridgeline is cut through with steep valleys, constantly ascending and descending.

Now, imagine traversing that path all night, in full battle gear, moving silently through unfamiliar, hostile territory, and then arriving at dawn ready to fight (and win) a major battle. It’s no wonder Sakuma chose to rest his exhausted troops at Oiwayama rather than press on to Shizugatake. Unfortunately, that hesitation would prove fatal.

For all his tactical genius, Hideyoshi was caught off guard. Shibata’s generals were experienced in rugged, mountaintop warfare, while Hideyoshi preferred lowland sieges. If Sakuma had pressed the attack and moved into Shizugatake Fort, and Shibata had fully committed to this maneuver, Maeda Toshiie might not have withdrawn. Seeing the entire secondary line collapse behind them, the former Nagahama retainers may have defected or at least withdrawn, turning the tide of this battle - and possibly Japanese history itself.

1 Dates used here are in the old Japanese lunisolar calendar. A few modern dates (Gregorian calendar) have been added in parentheses at critical points for reference. This is especially important regarding the season and snowfalls for this region.

2 You may see some photos of the remains of this embankment still online today (and a marker on Google Maps), but when I first visited in 2023, it looked like it had just been leveled and no trace remained in 2025.

3 In Japanese, the use of fort (toride 砦) vs. castle (城) differs widely for some of these locations. There is no common rule for naming. I used castle for the main bases and fort for the rest. Naming these as forts does not mean they are any less interesting. They are bigger and employ more advanced techniques than many castles I have visited. The Hideyoshi forts in particular showcase many features typical of the "shokuhoukei" castles (織豊系城郭) and fortifications of the period. The castles profiled here were largely abandoned following the battle, preserving the strategic design of castles from that time.

4 The “Seven Spears” is an interesting aside to the story of Shizugatake. The title comes from Edo-period romanticized accounts of their valor, and may exaggerate their individual roles in the battle. Hideyoshi himself promoted their reputations as part of a broader effort to elevate his loyal commanders and shape a heroic legacy.

Field Notes[edit]

This brief article marks the culmination of six trips to the Yogo region over two years (Apr ’23–Apr ’25). For various reasons, I wasn’t able to complete them all in a single season. The weather is unpredictable, with heavy snowfalls that often linger on the mountaintops well into spring, just as they once did during the actual campaign! I was also researching as I went, adjusting plans and making exploratory forays to confirm certain sites along the way.

There are still a few places I would have liked to reach, but with enough ground covered and the key locations documented, I finally had the material needed to shape a coherent narrative. I will revisit the region someday and document more of the smaller outlying forts but they are mostly one-off's that would require a full day just to reach one small site.

With a bit of hiking and light mountaineering, all the sites profiled here were fairly accessible. Trail conditions varied, but nothing was unreasonably difficult, except perhaps the steep and slippery slope from Besshoyama Fort to Gyoichiyama Fort, which I ultimately had to give up on. (I was also recovering from an injury after taking a tumble at Shobudani Fort and running out of time after spending too long at the lower forts!). Public transportation in this region is nearly non-existent. I made all these visits by renting a bicycle from either Yogo Station or Kinomoto Station. For more on access and hiking conditions, see the individual castle profiles.

Special thanks go out to RaymondW who first got me interested in the great sites out here around Lake Yogo and convinced me to explore further more of the depths of Shiga Prefecture castledom. Also, special kudos go to castle researcher Hiromi Hasegawa for the fantastic signboard maps found at many sites around Lake Yogo. Some are featured above. He should really have a book of his own about this area!

With this series, more than ever, it hits home why we visit castles. You can read about battles and castles in books, you can pore over maps, but nothing compares to walking the terrain, seeing what's out there and drawing your own conclusions. I found some texts about the Battle of Shizugatake lacking, even from well known authors. Castle articles muddle the history and history texts gloss over the castles. No one had walked the trails, visited the castles nor reflected on what they are writing.

As a castle fan, I wrote the article that I wanted to read. I hope you'll enjoy it too.

June 29, 2025

Bibliography[edit]

The following materials are primarily castle related books and were referenced in visiting castles for maps, directions, creating the castle profiles and understanding the historical landscape for this article. Some of the assumptions about individual castles and battle commentary are my own based on extensive reading and may not be explicitly stated elsewhere.

- 近江城郭探訪: 合戦の舞台を歩く

- 賤ケ岳の戦い (歴史群像シリーズ 15)

- 織豊系陣城事典 (図説日本の城郭シリーズ6)

- (図解)近畿の城郭I~V

- 近畿の名城を歩く 滋賀・京都・奈良編

- 近江の山城を歩く

© This article is copyright by Jcastle.info.

Please do not reproduce it without permission. If you reference any quotes, ideas, or contextual insights from this piece, kindly provide appropriate credit and a link. Like all feature articles on this site, this work is the result of extensive research, library and field investigations, and a significant investment of time and resources to craft a cohesive, castle-focused narrative in English. Since no other English source presents this depth of detail on the subject, it’s likely that any future guidance (including ChatGPT or other GenAI) you encounter with this focus will likely trace its origins to here.

__NOEDIT__